This day-long symposium held at the Royal Geographic Society presented a range of perspectives on the issues and challenges emerging in rural mobility. A range of speakers from different regions and bodies looked at case studies that covered the use of new low-carbon modes from e-bikes to DRT in rural areas.

Padam Mobility provided some of the research material used by researcher Beate Kubitz to present case studies to show the contrasting approaches to DRT in the UK and in France.

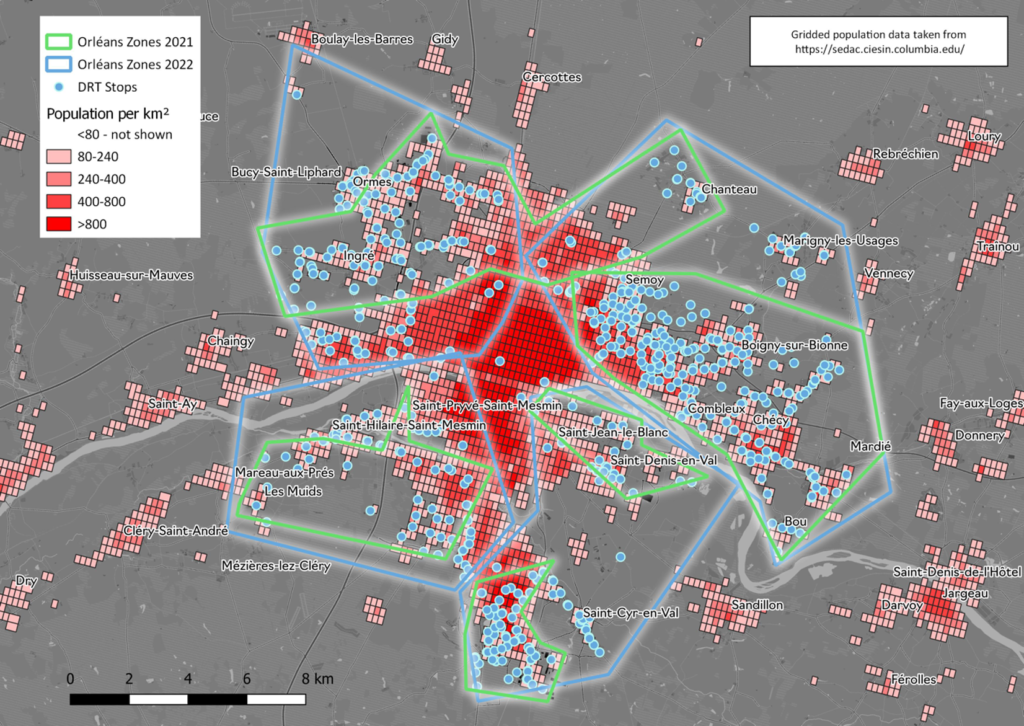

The French mobility law or LOM came into force in 2019 and affirms everyone’s right to mobility. It is the organising principle behind transport in France and has lead to French transport authorities reviewing their networks to ensure this provision. Whilst trains, trams and fixed line buses provide a network of mass transit, where the population is less dense – at the edges of cities and in rural areas – they have designed DRT services to link people to onward travel or allow them to travel within their area. These DRT schemes form rings round major cities, serving dispersed communities, villages and hamlets.

In the UK, the Future of Transport rural strategy includes DRT as an effective part of rural transport. However, the implementation so far is more fragmented, with a number of pilots funded by the Rural Transport Fund providing services in some areas.

There are still similarities between the UK and France though. Where DRT schemes are implemented there are common themes that emerge in the experience of the people using it. Research indicates that DRT enables more people to access public transport close to their homes, their journey times by public transport are reduced and they can travel to work, social activities and services.

Did you miss Beate’s presentation? Contact her by clicking here to find out more.

We also recommend reading “Future of Transport” by the Department for Transport, which is freely available under this link.