In collaboration with Community Transport Organizations FYT Bus on the Isle of Wight and Southampton’s Social Care in Action (SCiA) Dial-a-Ride; Solent Transport and its four local authority partners, have introduced a new mobile app for the Solent region to improve access to FYT and SCiA’s services.

Specifically, FYT’s on-demand service will cater to residents and visitors on the western side of the Isle of Wight, while members of Dial-a-Ride in Southampton will be able to book SCiA’s Dial-a-Ride service through the new mobile app.

Powered by Padam Mobility, a globally renowned provider of dynamic demand-responsive technology, the new journey planning app aims to offer seamless and convenient access to public transportation on the Isle of Wight and across Southampton. To access these services, users can download the “FYT and SCIA Booking” app from the App Store or Google Play, select their local service and book their journey..

This innovation in community transport within the Solent region has been made possible through the support of the Solent Future Transport Zone (FTZ) programme, funded by the UK Department for Transport. Collaborating closely with FYT Bus and SciA Dial-a-Ride, the Solent FTZ will monitor and assess the advantages of on-demand transportation solutions. This valuable information will contribute to shaping transport policies at a national level.

Introducing the “FYT Bus On-Demand Service”

The on-demand FYT Bus, also known as the “Route E afternoon service” or West Wight FYT Bus, will be running only in the afternoons and aims to cater to the transportation needs of residents and tourists on the picturesque, west side of the Isle of Wight. This cutting-edge on-demand service is designed to offer convenience and flexibility, with the inclusion of virtual stops and several fixed points served during each ride. Passengers will experience a new level of convenience, allowing them to reach their destinations seamlessly.

Enhanced Accessibility with the “Southampton Dial-a-Ride Service”

In addition to FYT’s Route E afternoon service, Padam Mobility is delighted to provide Southampton Dial-a-Ride members with access to the “Southampton Dial-a-Ride Service” within the same app. This service, offered in collaboration with the SCiA Group is set to improve public transport accessibility in Southampton and the surrounding areas by offering real-time bookings across a website, call centre and mobile app.

Padam Mobility’s cutting-edge technology and expertise will be harnessed to enhance efficiency, streamline booking processes, and simplify management for users of the Southampton Dial a Ride Service. Passengers can look forward to an improved and more user-friendly experience, making travel within the city and beyond more accessible than ever before.

About Padam Mobility:

Founded in 2014, Padam Mobility provides digital on-demand public transport solutions to transform peri-urban and rural areas and provide better access to mobility services for all.

To achieve this, Padam Mobility provides a software suite with intelligent and flexible solutions that better adapt public transport services to real demand, especially in sparsely populated areas. The software suite is based on powerful algorithms and artificial intelligence.

Public transport operators, public authorities and private companies trust Padam Mobility when it comes to improving access to territories, enhancing mobility services and optimising operations. The company accompanies its clients on the road to operational excellence while promoting environmentally friendly mobility.

Padam Mobility was acquired by Siemens Mobility in May 2021. The company is headquartered in Paris.

About Solent Transport:

Solent Transport is changing the way the public travels in the Solent area; making it greener, healthier and economically stronger than it’s ever been before. Through the delivery of transport solutions, Solent Transport provides leadership, strategy and direction to support sustainable economic growth in the Solent area. Originally established in 2007, Solent Transport is an apolitical partnership between the councils of the Isle of Wight, Hampshire County, Portsmouth and Southampton. In collaboration with the local community, business, government and transport operators, Solent Transport undertakes research; develops transport policy and strategy; submits and supports funding bids; and lobbies for transport improvements that will benefit everyone.

About the Solent Future Transport Zone:

Solent Transport won £29m from the Department for Transport (DfT) to implement innovative future transport solutions around personal mobility and freight movements. The funding means the Solent area will benefit from several innovative transport solutions including: smartphone apps for planning and paying for sustainable journeys demand, e-bike share scheme, and new approaches to freight distribution, including drone freight trials for NHS deliveries across the Solent to the Isle of Wight. Funding will be allocated to different projects across the region. The Solent Future Transport Zone programme proposes to address local challenges such as high levels of car usage and the environmental impacts of freight movement within Solent’s urban areas. It will do this by delivering a series of complementary projects within two key themes: Personal Mobility and Sustainable Urban Logistics.

This article might interest you as well: Enhancing Accessibility in Rural Cheshire West and Chester with DRT Service “itravel”

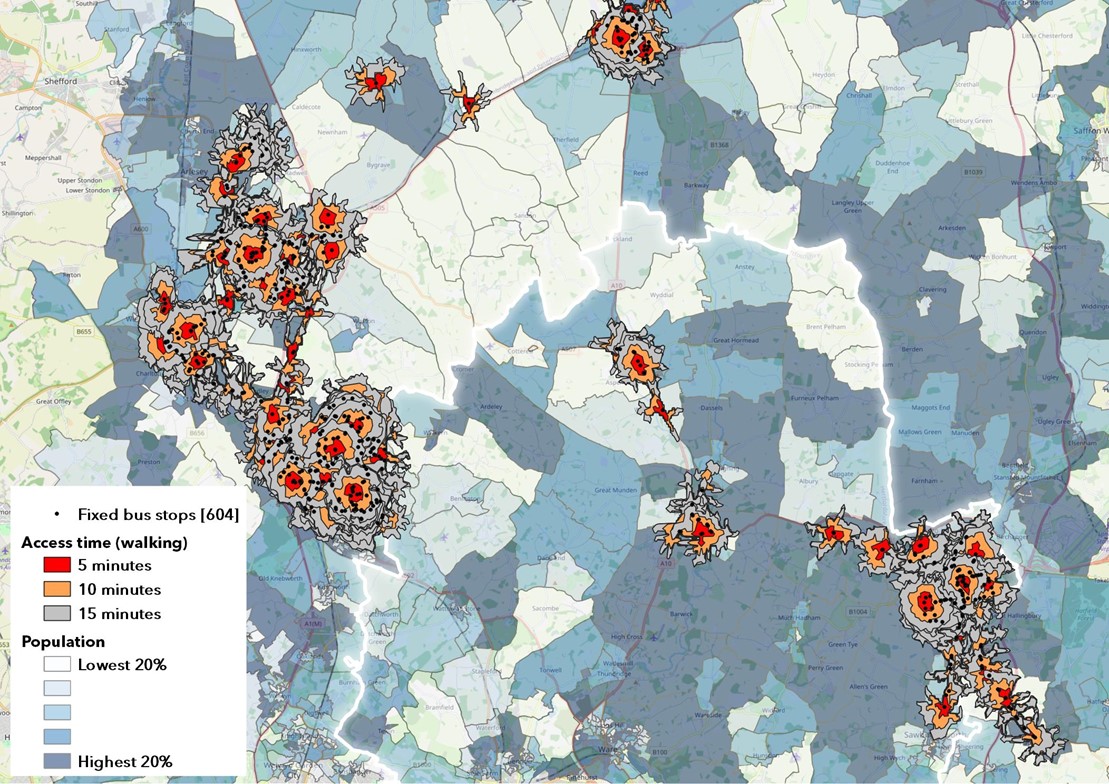

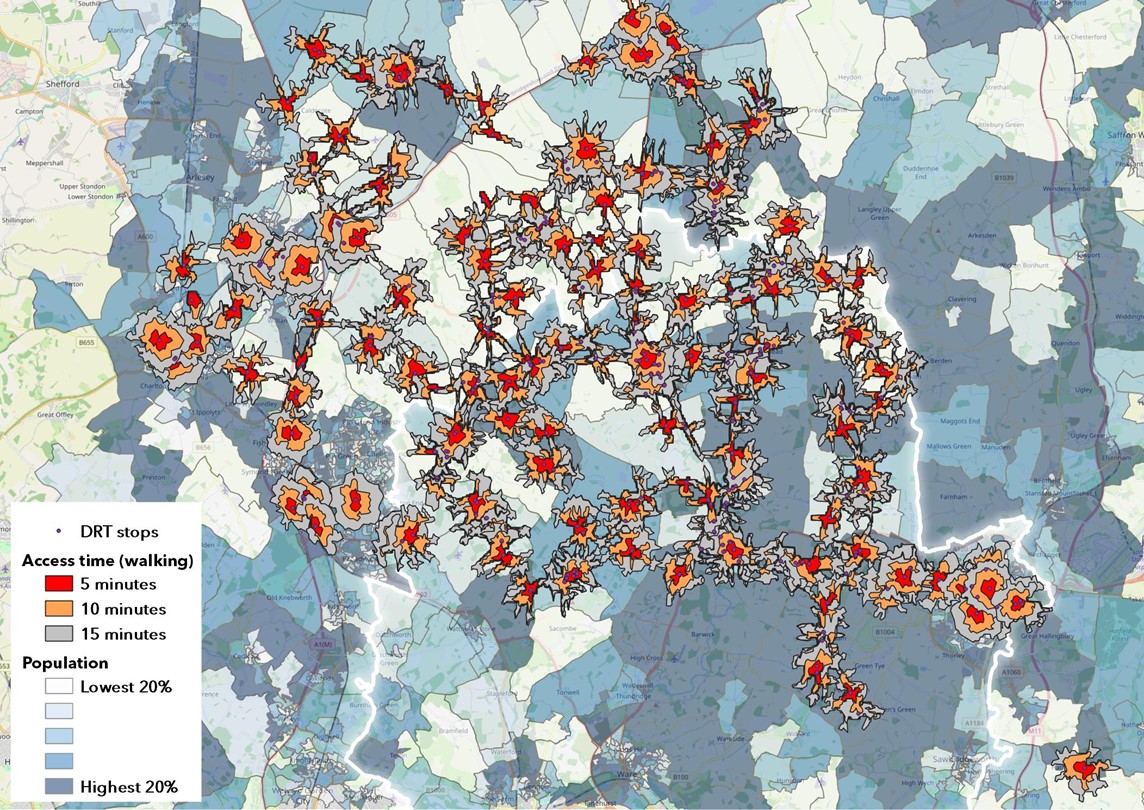

At the same time, analysis of transport stops in the area show them to be sparse. When it comes to bus stops that are served hourly

At the same time, analysis of transport stops in the area show them to be sparse. When it comes to bus stops that are served hourly