“Surrey Connect” is a new on-demand service, launched by Padam Mobility in the UK. It offers residents in rural West Leatherhead a better public transport experience.

At the beginning of November 2021, “Surrey Connect”, the new Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) service in West Leatherhead, was officially launched. The service has been in trial operation since May and has now been introduced to the local community by Surrey County Council. The new DRT service has received a contribution from the Department for Transport Rural Mobility Fund of £660,000. This reaffirms the UK’s commitment to its new mobility strategy and sends an important signal for future-oriented, sustainable transport.

“Surrey Connect”, equipped with a fleet of 2 minibuses, is operated by Mole Valley District Council and is available weekdays from 7 am to 6 pm. The on-demand service is aimed at travel for all: elderly people who can no longer be independently mobile, young people without alternative means of mobility or commuters travelling to the station to catch a train, for example.

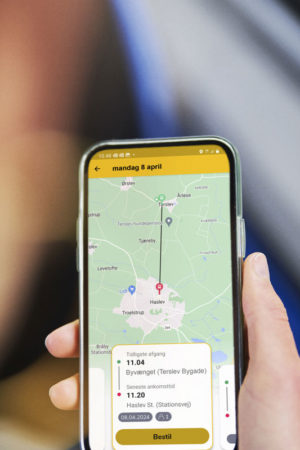

Several booking options are available on the Padam Mobility platform and users can book a trip according to their preferences, either via the “Surrey Connect” app, booking website or call centre. Tickets can then be paid for in cash on the bus.

One particularly user-friendly aspect of the service is the flexible booking time. Users can book a trip up to 7 days in advance, and their place is guaranteed according to a first-come, first-served logic. Those who want to make a last-minute reservation can do so up to 30 minutes before departure. All they have to do is set up their starting point and destination, as well as their desired pick-up or arrival time. Padam Mobility’s intelligent algorithms, on which the on-demand service is based, then calculate an optimal route in real-time based on the total amount of bookings. In this way, the system is able to consider as many of the users’ requests as possible simultaneously, while economising on resources.

People with reduced mobility, who use a wheelchair, for example, can also specify their requirements in the app, on the website or while booking a trip over the phone. This ensures that everyone gets exactly the support he or she needs.

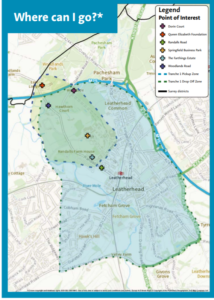

So far Surrey Connect is available in Leatherhead within the designated zones (see Figure 1), but will be rolled out to other areas of the region in the coming year.

*Following a free-floating model, it is possible to travel to any location within the two marked zones. Only bookings from one zone to the other are permitted. The markers show the main points of interest in the area, which includes, for example, the Springfield Business Park.

This service model provides rural areas in Leatherhead with much better connectivity where reliable access to public transport was previously unavailable.

I am delighted that we are now able to offer this convenient, doorstep service for residents in West Leatherhead. This will help people who may be isolated due to their out of town location or have had to traditionally be heavily car dependent.”

Matt Furniss, SCC Cabinet Member for Transport and Infrastructure

Visit the website of Surrey County Council

WHY PADAM MOBILITY?

- Empowering non-motorized populations in their travel (seniors, minors, etc.)

- Reducing dependence on the private car and its negative impacts (pollution, maintenance costs, etc.)

- Opening up certain low-density areas by providing a public service accessible every day Improving access to services and jobs, in particular improving access to health facilities

- Digitalising the territory with the introduction of a solution based on optimisation algorithms thanks to artificial intelligence, but also on user-friendly interfaces

ABOUT PADAM MOBILITY

Established in 2014, Padam Mobility provides digital on-demand public transport solutions (DRT, Paratransit) to reconnect peri-urban and rural areas and bring communities closer together. To do this, Padam Mobility provides a software suite of smart and flexible solutions that improve the impact of mobility policies in sparsely populated areas for all types of users. To get users, operators and Local Authorities on the move. This software suite is based on powerful algorithms and artificial intelligence. It includes :

- Booking interfaces (mobile app, website) for users and call centres

- A navigation interface (mobile app and tablet) for drivers

- A management interface for operators and Public Transport Authorities

- A simulation tool for designing and setting up mobility services

Transport authorities, operators, private companies and consulting firms trust us to open up territories, to optimise the mobility offer and facilitate its operations, to accompany them towards operational excellence, and finally to enable environmentally-friendly mobility.

Key figures:

- +470 000 users transported in 2020 (already 365 000 users transported at the beginning of 2021) more than 1M users transported since our creation

- +70 territories deploy our solutions in Europe, Asia and North America

- 80% pooling rate in average

- Up to 3.3 x less expensive than a similar offer if operated by fixed lines

- 33% of our users were previously using private cars, 19% were walking or unable to get around

Website | LinkedIn | YouTube |Twitter

This article might interest you: With HertsLynx Padam Mobility continues its expansion in the UK